Research Scholar

School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU

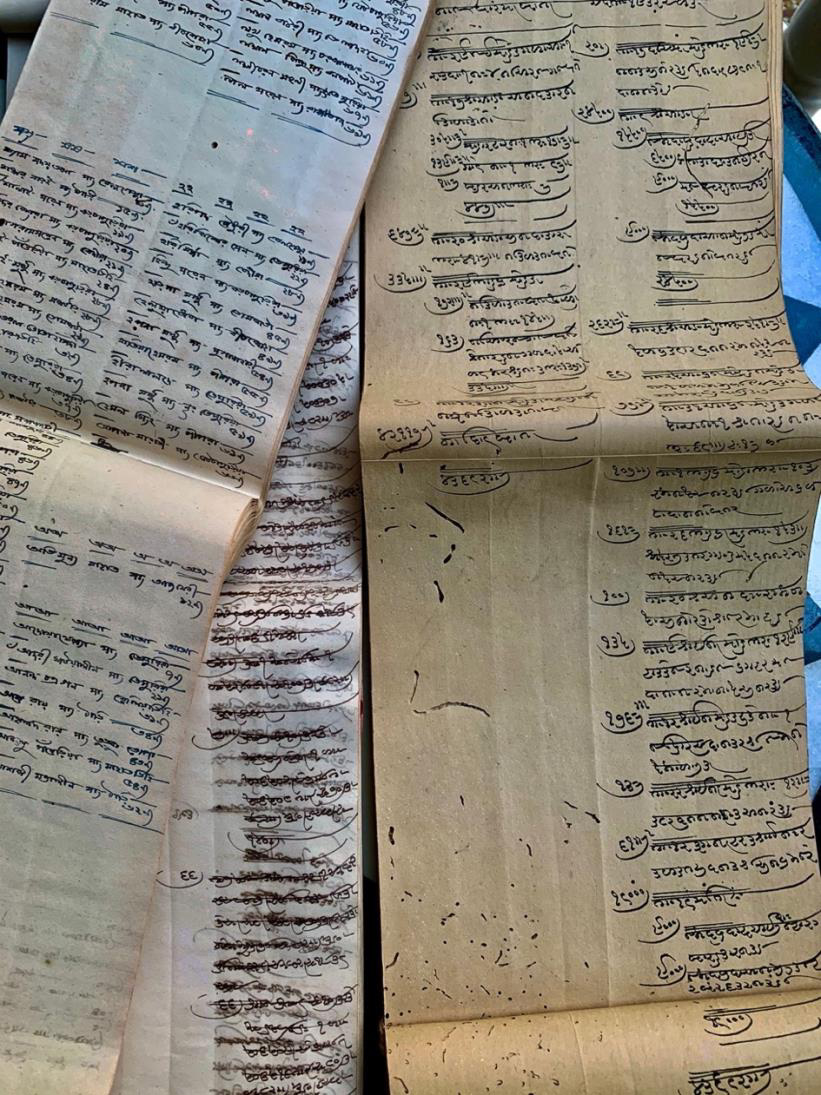

Fig 1: Bahi Khatas from the Dudhoria Family Archive, Azimganj, Murshidabad. Photo : By Author, March 2021.

Bahi Khatas or traditional accounting registers whose history predates many centuries made a sensational comeback when the Indian Finance Minister Mrs. Nirmala Sitharaman sported a red silk bag (with the national emblem) representative of a traditional red soft bind accounting register thereby making a major departure from the practice of carrying a briefcase to present the Union Budget in the Indian Parliament. While some saw it as a overturning of an age old colonial practice in favour of revival of a truly traditional Indian

heritage, others dismissed it simply as a gimmick. Whichever way one would want to interpret it, it brought to the fore the significance of Bahi-Khatas as a very remarkable source of reconstruction of our past. Focusing on some Bahi-Khatas from the personal family archive of the Dudhoria Family of Azimganj, this essay will thus go on to explore the nature of this material as a source for reconstruction of the past and from it we will investigate how it sheds light on the swiftly changing nature of Jain identity formation in late 19th -early 20th Century Bengal.

The history of the Jain migration to Bengal takes us back to the eighteenth century. One mostly associates the Jain settlers of Bengal with the Jagat Seth line of merchants and bankers who had migrated from Marwar to Azimabad ( erstwhile Patna) as early as the 17th century. Having played a crucial role in organization and supervision of revenue collection and management of the treasury of the Bengal Nawabs of Murshidabad, the Jagat Seths’ banking network functioned in a cash-strapped economy facilitating from the Mughal Emperor in Delhi to the different East India Companies that were based in and around the then Bengal capital of Murshidabad. The mid eighteenth century was a turbulent political period with the Battle of Plassey in 1757 followed by the Battle of Buxar in 1764 and the transfer of Bengal’s Dewani to the English East India Company in 1765. This period also witnessed a steady influx of the Jains from western India and Rajasthan who emigrated to Bengal marking the second wave of Jain migration in the province. The period after 1765 saw

a rise in the arrival of Rajput Ksatriya Jains who formed banking and financial networks independent of the Jagat Seths. They came to be known as the Sheherwali (urban) Jain community of Murshidabad who quickly went on to become zamindars in Azimganj and Jiaganj, areas adjoining Murshidabad. During the 19th century, with a steady decline in status of the Jagat Seths, the Sheherwali Jain community went on to become icons of wealth and pomp in Murshidabad playing a prominent role in the political, economic, social, cultural and religious life of the area ever since.

Earliest records of the Dudhoria family takes us back to the year 1774 when Hajrimal Dudhoria and his two sons, Sabai Singh Dudhoria and Maujiram Dudhoria emigrated from Bikaner in Rajputana to settle in Azimganj in Murshidabad. Initially engaged in country made cloth business, the family’s fortunes and prosperity took off with Babu Harek Chand Dudhoria who not only extended the mercantile reach of the family but also went on to establish a banking business in Calcutta, Sirajganj, Azimganj and Jangipur. As bankers and money lenders the family now commanded an impressive credit and trading network that was further facilitated by the changing nature of the colonial economy, commercialization of agriculture, changing land policies and the payment of regular taxes. Hence, it does not come as a surprise that the Dudhoria family soon gained many attributes which would make them influential figures in the Azimganj-Murshidabad area. They had wealth, extensive credit control, important marriage and kinship ties, access to supra local social networks in the area. All of these makes them an excellent point of reference through which one can explore the political and social developments as well as delve deeper into the various historical experiences in this area.

WHAT IS A BAHI-KHATA?

The word bahi (at times spelt as vahi) has three traditional meanings :

1. A book of genealogy

2. An account book

3. A book in general.

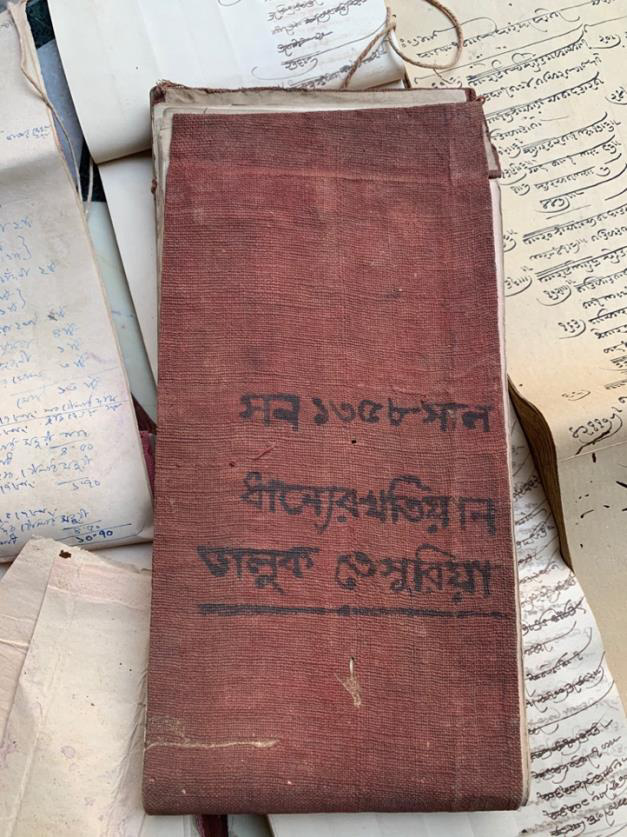

Fig 2. Cover image of the Bahi Khatas. Dudhoria

Family Archive, Azimganj. Photo: By Author, March 2021

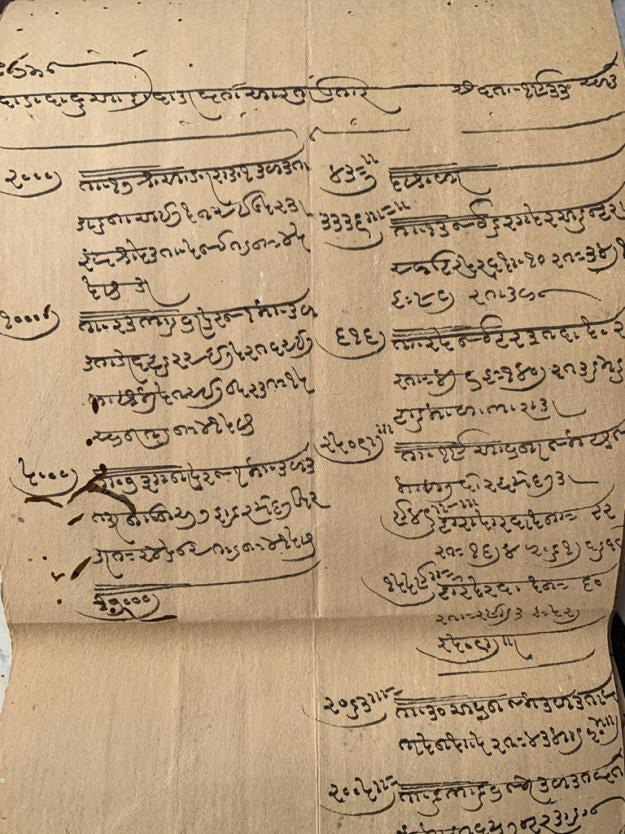

Fig 3. Folio from the Bahi Khata written in Marwari. Dudhoria

Family Archive, Azimganj. Photo : By Author, March 2021.

The sense in which we will contextualize our understanding of bahi-khatas is that of an account book. The book keeping practice found in traditional bahi khatas originated in Western India and was much in use in the regions of Gujrat and Rajputana. It usually has a double entry accountancy system that was mainly used by members of the mercantile communities, who were often peripatetic. Made of loose, long leaves of country made paper the bahi-khatas are from two to three feet long, and six to twelve inches broad, they are stitched together with a cloth cover of usually red colour by piercing the pages at one end, the books are then folded in the middle, and tied together by a cord ( Fig 2).

As an account book the bahi khatas were kept to maintain records of expenditures and incomes and it was kept in the estate offices where they were filed according to subject and dates. The bahis reveal a high level of bureaucratic competence in account keeping knowledge that mercantile groups from Rajputana brought with them when they emigrated to Azimganj. This is what makes them a very interesting historical material to explore how the people, their knowledge systems migrated and shaped their swiftly changing identities as emigres to the province of Bengal.

After a long perusal of the bahi khatas in the Dudhoria family archive which is literally stacked with hundreds of these accounts book, I could come to two very significant historical observations. Firstly, the early bahi khatas were written in traditional Marwari script of the 18th century ( Fig 4). Secondly, by the late 19th century a linguistic shift in the book keeping system can be witnessed, where maintaining the double entry system we find the language of book keeping changing from Marwari to the Bengali script (Fig 5).

Fig 4 : Folio from Bahi Khatas written in Marwari. Dudhoria Family Archives. Azimganj. Photo : By Author : March 2021.

Fig 5 : Folios from bahi khatas maintaining the double entry system but written in Bengali. Dudhoria Family Private Archives, Azimganj. Photo : By Author, March 2021.

These observations naturally indicate a historical development not only in the status of just the Dudhoria family but can be further juxtaposed to be understood as a larger sociocultural marker of the Sheherwali Jains in general. The linguistic shift from Marwari to Bengali makes it obvious that the family was no longer functioning as emigres in this area. By the mid 19th century they could be considered as settlers who had undergone a process of acculturation, in different aspects of their lives : from their diet and cuisine, costumes and habits to even their linguistic development. This was part of a larger social process of acculturation of the Marwari Jaina community in Bengal that has been the key factor behind their consistently shifting identity as they kept adapting to the socio-economic and political changes to continue wielding trading and financial power through the 19th and 20th century. Even today, they command significant wealth and prosperity not only in Azimganj and the Murshidabad area, but beyond.

The purpose of this essay has been to bring to the fore these rich historical documents that can form the basis of serious research which has remained rather neglected in the academic pursuits on Bengal. On top pf that my stress on the bahi khatas and the shift in its linguistic development is primarily to highlight the rich historical experience of migration and acculturation that had contributed to the cosmopolitan fabric of Bengal’s society since the early modern times to the present days.