A CASE STUDY OF THE DURBAR HALL OF THE BARI KOTHI

Research Scholar

School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU

The Jaina community being a mercantile and chiefly trading community have been long known for their mobility and cosmopolitanism through the centuries. The earliest record of the Dudhoria family takes us back to the year 1774 when Hajrimal Dudhoria and his two sons, Sabai Singh Dudhoria and Maujiram Dudhoria emigrated from Bikaner in Rajputana to settle in Azimganj during the second wave of Jaina migration to Bengal in the latter half of the eighteenth century that predominantly saw the migration of the Sheherwali Jainas from Rajput lands to Bengal. Initially engaged in country made cloth business, the family’s fortunes and prosperity took off with Babu Harek Chand Dudhoria who not only extended the mercantile reach of the family but also went on to establish a banking business in Calcutta, Sirajganj,

Azimganj and Jangipur. As bankers and money lenders the family now commanded an impressive credit and trading network that was further facilitated by the changing nature of the colonial economy, commercialization of agriculture, changing land policies and the payment of regular taxes. Hence, it does not come as a surprise that the Dudhoria family soon gained

many attributes which would make them influential figures in the Azimganj-Murshidabad area.

The impressive, newly and deftly restored building of Bari Kothi today boasts of a long heritage of wealth and grandeur of the Dudhoria Family. The architecture, representing an eclectic style of Western inspired as well as the typical ‘Marwari architecture’ of havelis mostly seen in Rajasthan stands out remarkably in the small hamlet of Azimganj. While, the owner of the building, proprietors of this heritage hotel, have brought to the fore for the visitors the rather spectacular narrative of how the building was given a new lease of life through the sustainable conservation and restoration processes what has been left out is an understanding of the stylistic elements that this house beholds. Delving into the stylistic understanding of what they call as the ‘Durbar hall’ that has now been transformed into a magnificent dining hall for the guests this essay will focus on a the tile program of the room that gives it a character and significance of its own.

At first glance, the Durbar hall’s ornate chandeliers, the long table decorated with finely crafted porcelains are bound to take one’s breath away. However, what stood out for me was the fabulous use of tiles in the interior decoration of the room that contributed to its splendour and richness. To me, a researcher of art history, the first thought naturally went to the painted havelis of Shekhawati, where frescoes of various themes and subjects like mythological genre scenes, local legends, animals and plants adorns the exterior and interior walls of the havelis. The ubiquitous use of the tiles in the Durbar hall was in all likelihood meant to substitute this aesthetic desire in the absence of fresco painting artists, called chiteras who were the artistic hands behind the wall paintings of Shekhawati; otherwise, it could have been that earlier on, at some point in the long history of this building there may have been wall paintings which has not stood the test of time and have hence been replaced by the more durable tiles, which are more easy to maintain and definitely more sturdy.

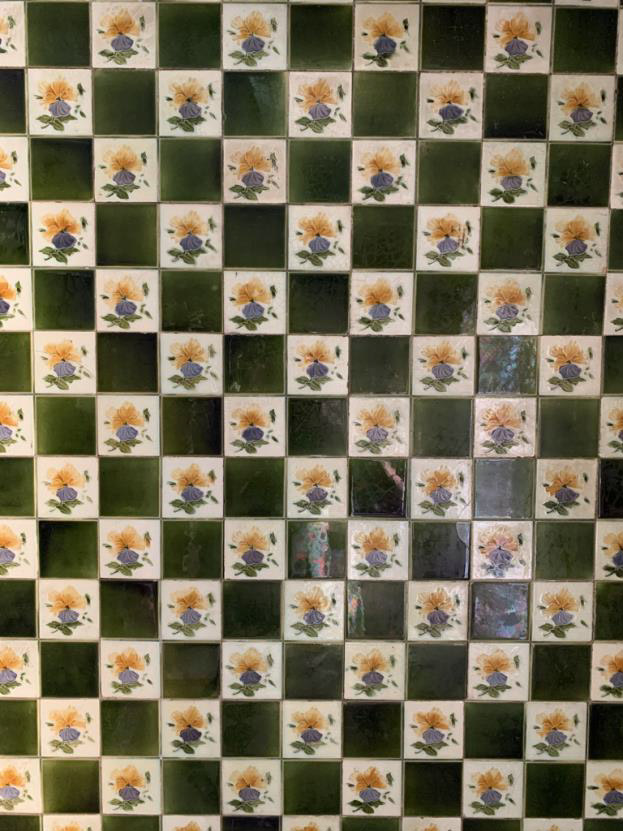

The tiles most extensively used in the Durbar hall can be identified as ‘MAJOLICA’ tiles. Majolica tiles are essentially glazed polychrome relief tiles with a decorative character and project the outlines of floral, faunal, geometric or other motifs and are glazed in multiple colours.

Image : Majolica tiles in the interior of Durbar Hall. Bari Kothi, Azimganj. Photograph : By author, 2021.

Image : Majolica tiles in the interior of Durbar Hall. Bari Kothi, Azimganj. Photograph : By author, 2021.

Image : Interior detail of the Durbar Hall, Bari Kothi, adorned with Majolica tiles. Bari Kothi, Azimganj. Photograph: By the author.

The interior walls of the Durbar Hall is decorated with various designs and forms of these polychrome relief majolica tiles bearing floral motifs. The tiles have partly come off the walls and the marks on the back are stamped on ground plaster. A keen survey of these marks enlightens us that in all probability these tiles were imported from Japan during the interwar period. Japan was a major exporter of what looked like British produced ‘Minton’ tiles but actually were Majolica tiles to India. In fact, so significant was the consumption of the Japanese majolica tiles in the then India that they would cater to the Indian visual aesthetics and iconographic program by incorporating designs, in particular tiles representing typically Indian genre scenes and Hindu mythological subjects that had a wide market among the wealthy classes here. This brings us to the most monumental decorative feature of the Durbar halls, the genre scenes on tiles that impressively commands one’s visual attention on all the four sides of the room.

Image : Indian genre scenes on majolica tiles in the interior of Durbar Hall. Bari Kothi, Azimganj. Photograph : By author, 2021.

Image : Indian genre scenes on majolica tiles in the interior of Durbar Hall. Bari Kothi, Azimganj. Photograph : By author, 2021

These tiles were custom made based on oleography or chromolithography prints of paintings ( academic paintings of the then India) that were very popular among the wealthy classes in India. Rich in colour, expressive, technologically advanced, striking as an interior decoration and essentially Indian in aesthetics - these easier to maintain relief tiles add a touch of historical specificity to the heritage of Bari Kothi that has remained unnoticed till now.

The larger historical and social implication of the usage of these tiles in the Bari Kothi is embedded very intimately in the Jain identity formation in Bengal. Reflective of a change in their aesthetic aspiration it is intertwined with a shift in their social status from simply being provincial merchants and successful traders to leading financers, bankers and early capitalists functioning in a colonial economy. In this light, the tiles maybe further understood to have functioned as a form of self-representation of the community in a time when their roles were shifting swiftly keeping up with the contingent socio-political and economic dynamics of the state. Thus, what the tiled walls of Bari Kothi beholds, is not just of artistic and aesthetic value but deeply reflective of a complex socio-political transition witnessed by this marvelous building.